HY-FOLIC®: THE KEY TO OPTIMAL HEALTH FOR THE ELDERLY

Indonesia has entered the era of an aging population since 2021, with the elderly population continuing to increase. According to data from the Central Statistics Agency (BPS), approximately 12% or 29 million of Indonesia's population are elderly. This figure is projected to rise to 20% by 2045. (1)

A study indicates that, on average, 30% of individuals aged 65 years and older experience folate deficiency. This condition can lead to various increased risks of chronic diseases that have negative impacts on the elderly, including:

(2,3,4,5,6)

Folic Acid Deficiency in the Elderly and the Role of 5-MTHF

Folate (vitamin B9) deficiency is mainly caused by insufficient folate intake and metabolic disorders due to genetic mutations of the enzyme that metabolizes it (MTHFR enzyme). This condition requires folic acid supplementation, especially 5-MTHF (Active Folate) supplementation, which can increase folate levels more quickly and measurably because active folate does not go through the four stages of metabolism. (12,13,14)

In the body, not everyone can metabolize folic acid into 5-MTHF (Active Folate) with the same efficiency. In other words, folic acid supplementation is not effective for some people. As a result, unmetabolized folic acid (UMFA) will be detected in the bloodstream, where UMFA is associated with several health problems.

This is due to genetic variations in the MTHFR (methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase) gene, which produces the enzyme responsible for converting folic acid into 5-MTHF. According to studies, 25% of the global population and 42% of the population in Southeast Asia, 37.1% in Indonesia have genetic variations/polymorphisms in the MTHFR C677>T and A1298>C enzymes, which hinder this process, so that folic acid cannot be optimally metabolized into the active form. (15)

As a result, even after taking folic acid supplements, individuals with MTHFR polymorphism remain at high risk of folate deficiency.

HY-FOLIC® does not require this conversion process, as it is already in its active form and can be used immediately. Therefore, HY-FOLIC® could be a effective solution to overcome folate deficiency.

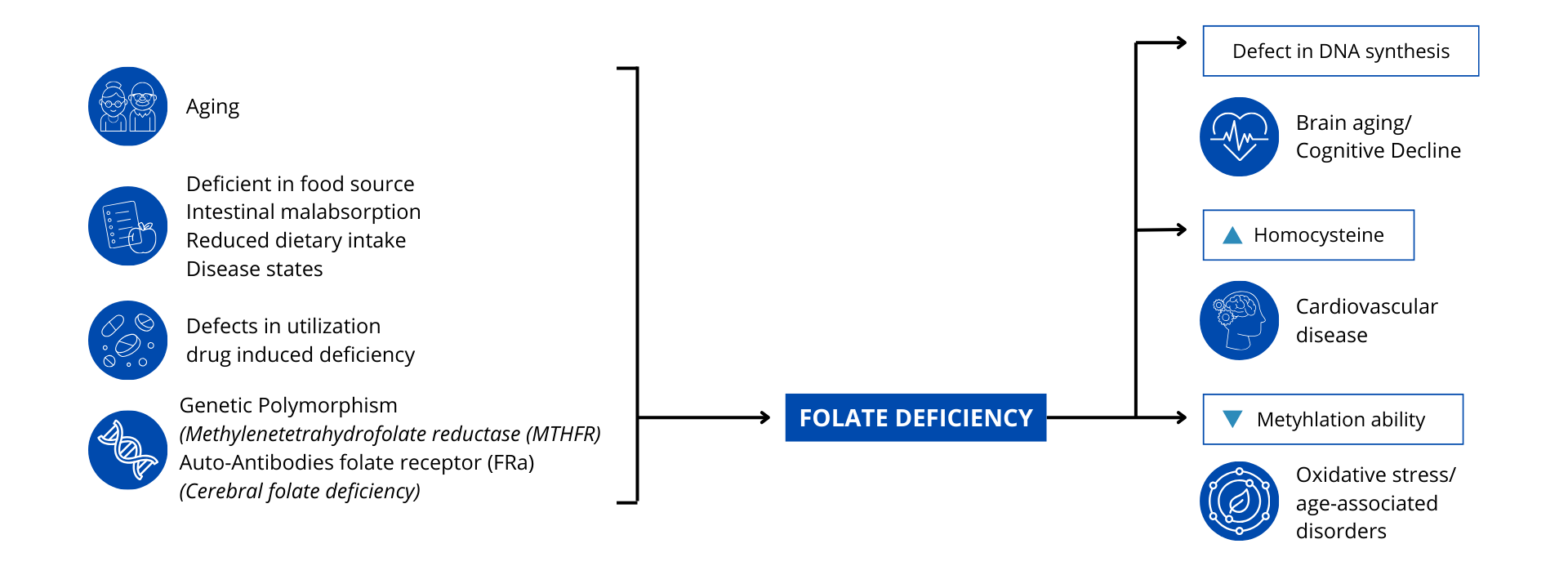

There are several factors that can cause folate deficiency, including:

Aging: As we age, our bodies' ability to absorb and utilize folate may decline.

Folate deficiency caused by:

Intestinal Malabsorption: a condition in which the intestines cannot absorb nutrients properly, including folate.

Insufficient Intake from Food: Food intake that does not contain enough folate.

Medical Conditions: Some diseases can affect the absorption or metabolism of folate.

Folic Acid Deficiency Due to Medications: Certain medications can interfere with folic acid metabolism or availability in the body. Examples include antidepressants, anticonvulsants, methotrexate, antimalarials, and PPIs, which can reduce folic acid availability in the body.

Genetic Polymorphism:

Mutations in the MTHFR gene can reduce the body's ability to convert folate into its active form (5-MTHF) that can be used.(18)

In addition, folate deficiency can cause several serious health problems, including:

(19,20)

Hyperhomocysteine and Cardiovascular Disorders in the Elderly

Homocysteine is an amino acid formed from the metabolism of methionine. 5-MTHF is the active form of folate involved in the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine, a process that is very important for maintaining normal homocysteine levels in the body. In addition, this process also plays a role in the expression of DNA formation genes in methylation reactions. Methionine metabolism occurs through one-carbon metabolism, which requires 5-MTHF (active folate), vitamin B6, and B12. However, this metabolic balance can be disrupted due to a deficiency of 5-MTHF (active folate).

Folate deficiency can occur due to insufficient intake of folate from food sources or supplements and genetic mutations in the MTHFR polymorphism. Disruption of homocysteine metabolism can lead to the accumulation of homocysteine in the blood (hyperhomocysteinemia) [21]. Cross-sectional studies examining homocysteine, vitamin B, and stroke indicate that vitamin B levels should be increased and homocysteine levels reduced to prevent stroke [22].

Hyperhomocysteinemia is a condition where homocysteine levels in the blood are outside the normal range of 5–15 mmol/L. Hyperhomocysteinemia is categorized into three stages: mild (15–30 mmol/L), moderate (30–100 mmol/L), and severe (>100 mmol/L).

Hyperhomocysteine can cause various health problems. If left untreated, this condition can trigger heart diseases such as atherosclerosis and stroke. This occurs because homocysteine is toxic to blood vessel endothelium, increases LDL oxidation, and triggers blood clot formation [23].

Endothelial cells in blood vessels act as regulators of blood circulation homeostasis and blood vessel walls, functioning like gatekeepers of heart health. Endothelial cells play a crucial role in regulating blood vessel wall homeostasis, including vascular tone, coagulation, inflammation, and permeability. As cells directly exposed to blood, endothelial cells are susceptible to damage from various risk factors that can lead to endothelial dysfunction and endothelial barrier damage. This damage can trigger a series of domino effects on heart health, such as inflammatory responses, monocyte recruitment, plaque formation, structural changes in the heart, and thrombosis (blood clot formation).

Based on studies, it indicates that hyperhomocysteinemia can damage endothelial cells and cause endothelial dysfunction. Several other studies confirm that homocysteine concentration is associated with atherosclerosis. Clinical studies show that plasma Hcy levels in patients with coronary artery disease are significantly higher than in control groups with normal angiography results. Even elevated plasma Hcy levels, even if only 12% above the upper normal limit, have been associated with a 3.4-fold increase in the risk of myocardial infarction (heart attack) [23].

A study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC) in 2024 found that homocysteine (tHcy) levels were positively associated with myocardial injury and cardiovascular mortality, further strengthening the link between HHcy and CVD events [24].

Another study by the International Renal Research Institute in Italy in 2017 found that 85% of patients with chronic kidney disease had hyperhomocysteinemia [36]. This reinforces the association between hyperhomocysteinemia and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and kidney damage.

Folate Deficiency Causes Hyperhomocysteinemia

Folate deficiency can lead to elevated homocysteine levels in the blood, which is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and kidney damage.

Clinical Evidence of the Benefits of Folate for Cardiovascular Health

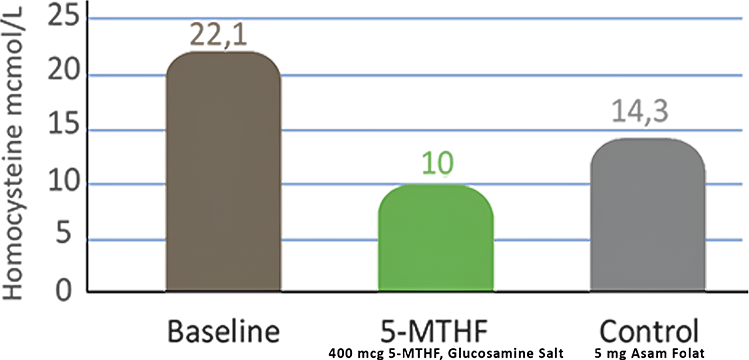

Folate supplementation has been shown to be beneficial in reducing the risk of stroke (prevention) and managing blood pressure through the reduction of hyperhomocysteinemia. A clinical study by Mazza, A., et al. in 2016 showed that administration of 5-MTHF (Active Folate) 400 mcg can reduce homocysteine levels by up to 55.8% compared to baseline conditions [25].

Image. Comparison of the effectiveness of 5-MTHF (Active Folate)

in reducing homocysteine compared to folic acid.

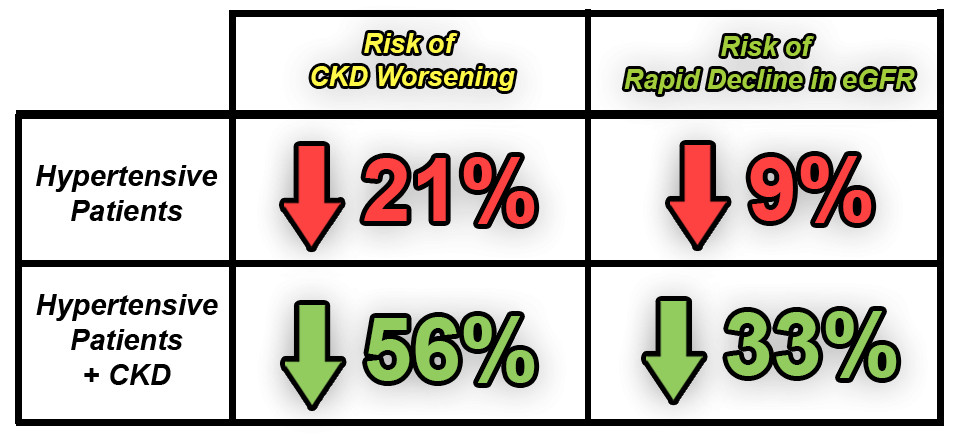

Another large-scale study in China, involving more than 20,000 hypertensive patients, showed that the use of folate in patients receiving antihypertensive therapy can significantly reduce the incidence of stroke and progressively reduce the risk of kidney function [26].

Evidence Based

The study by Huo, et. al. (2015), showed that folate administration in patients receiving antihypertensive therapy (n=10,348) can reduce the incidence:

The study by Xu, et. al. (2016), showed that folate administration in patients receiving antihypertensive therapy can reduce the incidence:

Folic Acid Supplementation Can Improve Heart Health

Folate supplementation can improve heart health and prevent the worsening of chronic kidney disease by lowering hyperhomocysteine levels.

Conclusion

HY-FOLIC® plays a crucial role in maintaining heart and blood vessel health through its ability to optimize homocysteine metabolism. As the active form of folate, 5-MTHF in HY-FOLIC® helps convert harmful homocysteine into methionine, thereby preventing the accumulation of high homocysteine levels or hyperhomocysteinemia. Given that hyperhomocysteinemia is a major risk factor for atherosclerosis, endothelial damage, increased LDL oxidation, and blood clot formation—which can lead to coronary heart disease and stroke—supplementation with HY-FOLIC® is an important strategy for mitigating these risks.

Solid clinical evidence shows that folate supplementation, such as that contained in HY-FOLIC®, can significantly reduce the incidence of stroke and the risk of worsening kidney function, confirming its role in the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease. Therefore, HY-FOLIC® can be an effective solution in maintaining overall heart and blood vessel health.

Folate, Brain Aging, and Cognitive Decline In The Elderly

A study by Bottiglieri and Reynolds in 2000 showed that folate concentrations in the brain—specifically in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)—decrease with age, particularly in elderly people over the age of 70. This provides evidence of a relationship between folate levels, age, and the nervous system. (16)

Benefits of Folate on the Nervous System

HY-FOLIC® supplementation can support brain function efficiently because it can meet the need for active folate with the right increase in dosage. HY-FOLIC® that contain 5-MTHF (Active Folate) is also the only form of folate that can cross the blood-brain barrier.

Folate deficiency has long been associated with brain dysfunction, including depression, dementia, and Alzheimer's disease. As a bioactive form, 5-MTHF has the ability to directly cross the blood-brain barrier and participate in important biochemical reactions in the central nervous system.

The Mechanism of 5-MTHF in Supporting Cognitive Function

5-MTHF acts as the primary methyl donor in the conversion of homocysteine to methionine, which in turn produces S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe), a key molecule in methylation reactions. This methylation is necessary for gene expression regulation, neurotransmitter production (such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine), and maintenance of neuronal integrity. Additionally, 5-MTHF supports the production of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), an important cofactor for neurotransmitter synthesis, which overall supports mood stability and cognitive clarity. (27)

The Impact of 5-MTHF Deficiency in Patients with Cognitive Impairment

A deficiency in 5-MTHF can increase homocysteine levels in the blood, which is neurotoxic and has been associated with an increased risk of dementia and brain atrophy. Individuals with MTHFR genetic mutations (particularly the C677T variant) experience impaired conversion of folate into the active form 5-MTHF, thereby increasing their risk of neurocognitive disorders. Additionally, medical conditions such as Helicobacter pylori infection can also affect 5-MTHF levels and exacerbate cognitive decline. (28,29)

Clinical Evidence of the Benefits of Folate for Cognitive Health

Various studies have shown that 5-MTHF supplementation has a protective effect on cognitive function. A systematic review showed that administering 5-MTHF to the elderly can lower homocysteine levels, improve executive function, and enhance working memory. Another study in an Alzheimer's mouse model showed that 5-MTHF reduces the accumulation of β-amyloid and phospho-τ, improves memory, and reduces oxidative stress in the brain.

A meta-analysis of 23 randomized clinical trials showed that folate-based vitamin B supplementation, including 5-MTHF, significantly improved cognitive performance, especially in countries that do not have food fortification programs with folic acid. This suggests that baseline folate status is an important determinant of treatment effectiveness. (30,31)

Compared to folic acid, 5-MTHF does not require enzymatic activation and is immediately available to the body, which is particularly important for individuals with MTHFR mutations. In addition, 5-MTHF avoids the accumulation of unmetabolized folic acid in the circulation, which can potentially have negative effects on immune and neurological function. Research also indicates that 5-MTHF is more effective in increasing brain folate levels than synthetic folate. (27,32)

Benefits of HY-FOLIC® for Delaying Brain Aging and Cognitive Decline

5-MTHF is an essential nutrient that supports neurological function through various biochemical mechanisms such as DNA methylation, neurotransmitter synthesis, and homocysteine level regulation. Deficiency in 5-MTHF has been shown to significantly impact cognitive decline, particularly in individuals with folate metabolism disorders. With higher bioavailability and greater efficiency compared to folic acid, 5-MTHF is a superior form of folate supplementation for addressing cognitive disorders.

Folate, Anemia, and the Elderly

According to the National Institute of Health, consuming large amounts of folic acid (generation 2 folate) can mask the destructive effects of vitamin B12 deficiency because unmetabolized folic acid (UMFA) can mask vitamin B12 deficiency. This means that blood tests we perform to detect Vitamin B12 deficiency may not show accurate results because Folic Acid (Generation 2) can occupy the receptors that bind Vitamin B12 without repairing nerve damage caused by Vitamin B12 deficiency. (37)

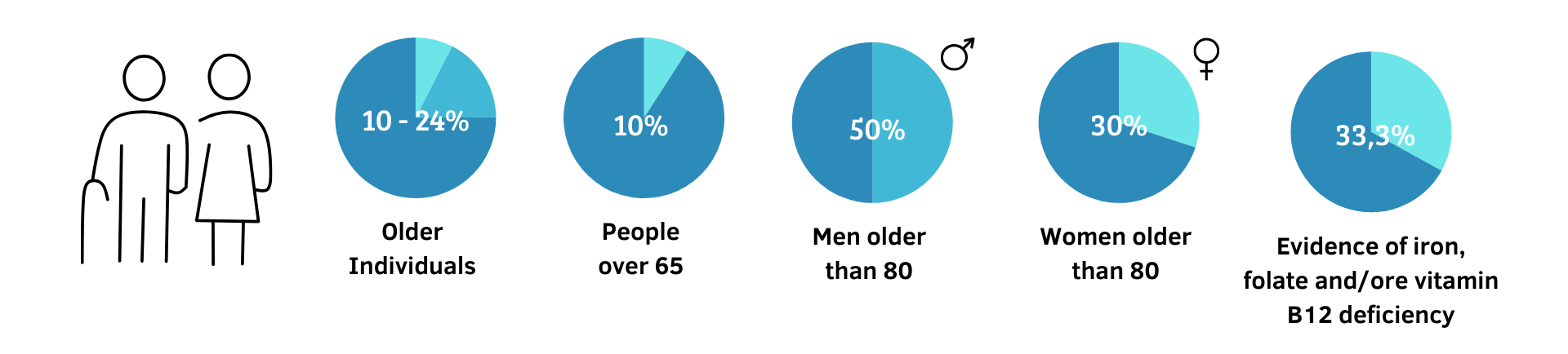

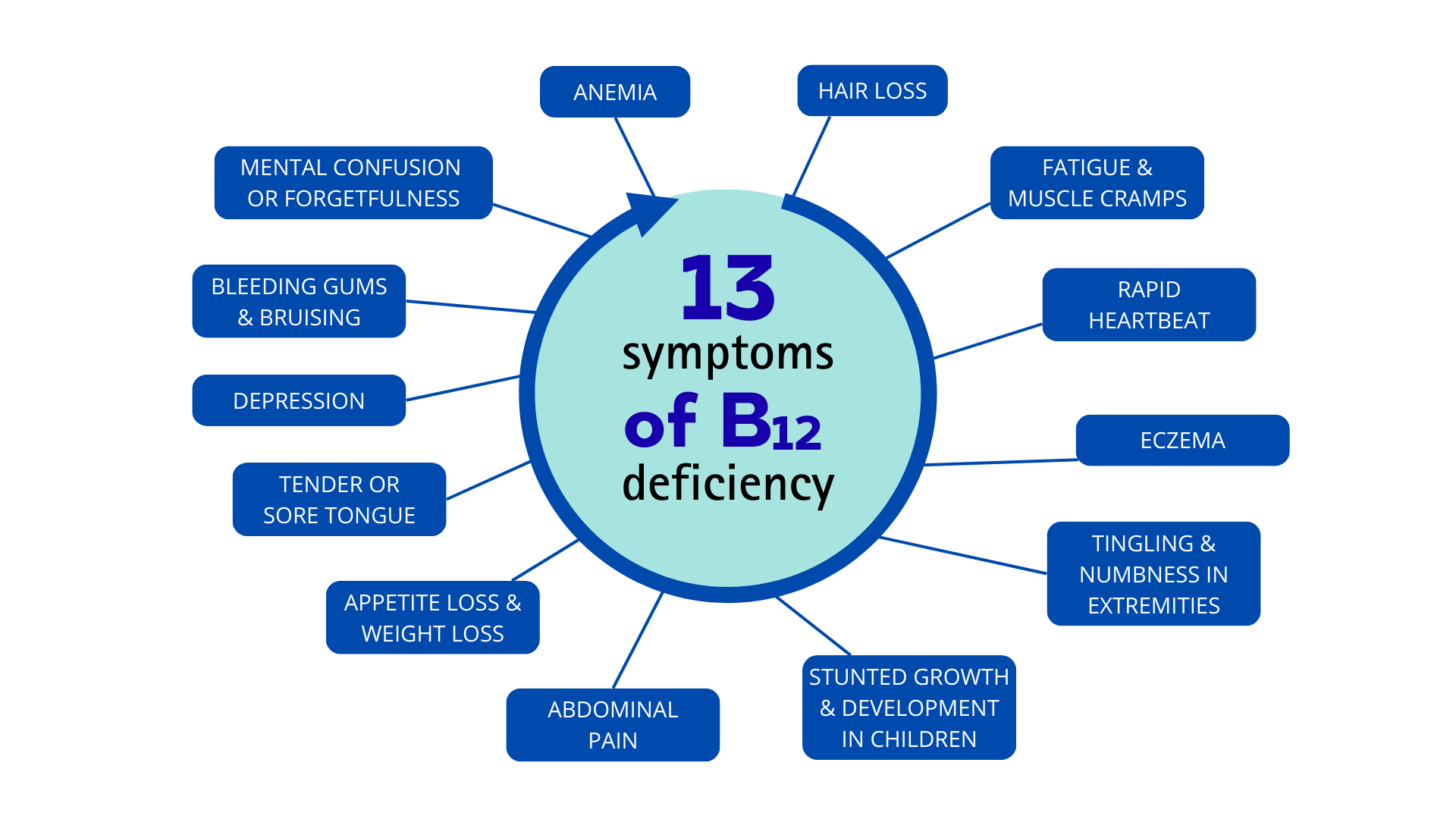

Based on studies, the incidence of Vitamin B12 deficiency in the elderly can reach 10–24%. In individuals over the age of 65, the rate reaches 10%. It is even higher in individuals over the age of 80, with an incidence of 50% in men and 30% in women. (37)

In the elderly, Vitamin B12 deficiency is common and often goes unrecognized. The most common symptom of Vitamin B12 deficiency is megaloblastic anemia, which can be improved after supplementation with large amounts of folate, especially in the elderly, where Vitamin B12 deficiency often goes undiagnosed. (34,35)

Meanwhile, HY-FOLIC® supplementation with 5-MTHF (Active Folate) will not mask the body's vitamin B12 status, resulting in significant benefits and a much safer profile than folic acid.

HY-FOLIC® Does Not Mask Vitamin B12 Deficiency

Supplementation with HY-FOLIC® is the primary choice for avoiding vitamin B12 deficiency, which can lead to various health problems.

Referensi: